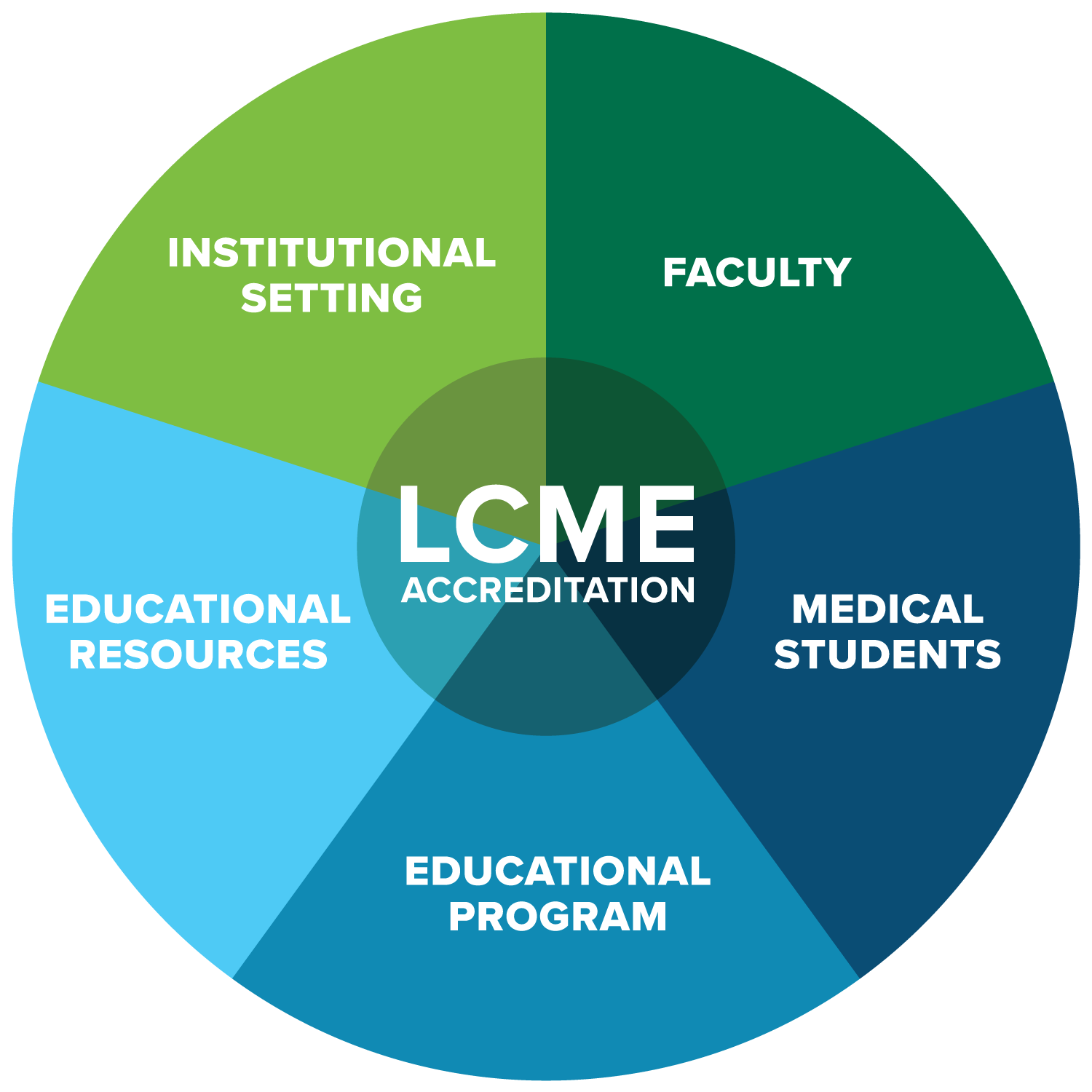

Accreditation demonstrates that the Heersink School of Medicine has met and is maintaining a high level of standards set by the LCME. There are 12 standards, divided into five areas: faculty, medical students, educational program, educational resources and institutional setting.Scaffolding adorned 7th Avenue side of Volker Hall for the past eight months as construction occurred on the building’s sixth floor. Did you know that project—and the building renovations coming later this year—all started with an accreditation visit?

Accreditation demonstrates that the Heersink School of Medicine has met and is maintaining a high level of standards set by the LCME. There are 12 standards, divided into five areas: faculty, medical students, educational program, educational resources and institutional setting.Scaffolding adorned 7th Avenue side of Volker Hall for the past eight months as construction occurred on the building’s sixth floor. Did you know that project—and the building renovations coming later this year—all started with an accreditation visit?

Re-accreditation from the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) is a way the UAB Heersink School of Medicine holds itself and its education programs accountable to established national standards. The LCME is the accrediting body for all MD-granting programs in the U.S. and Canada, so it’s standards help Heersink leaders benchmark our school against peer institutions and can guide changes to education programs and the learning environment.

So how does construction come in?

As a requirement from the LCME, the school is increasing the amount of small group, active learning in the pre-clinical curriculum and decreasing dependence on traditional lectures. To help facilitate this, the second floor of the Volker Hall Education Tower will be transformed into an active leaning center, designed specifically for small group and student directed instruction.

The planned active learning center features a “flipped classroom,” where students collaborate in small groups, using digital teaching tools, while the instructor moves between them.

“It’s important for us foster a learning environment where students collaborate and communicate to solve problems together, just as care teams do when they’re in the hospital or clinical settings,” said Craig Hoesley, M.D., senior associate dean for Medical Education and chair of the Department of Medical Education.

Hoesley said this is just one of many changes that have come to the school because of an LCME accreditation visit and the institutional self-reflection that takes place in preparation for those visits.

The school’s preclinical curriculum—once a topic-centered course structure—transitioned in 2007 to an integrated, organ-based curricular structure to give students a broader view of human health by infusing the topics throughout foundational Fundamentals courses, Introduction to Clinical Medicine and organ-based modules.

Curriculum updates in 2007 also brought about the formal inclusion of Scholarly Activity, which gives medical students the opportunity to explore research and academic scholarship throughout their medical school career, in addition to simulation, which students now engage in regularly.

The integrated pre-clinical curriculum continued to evolve throughout the school’s 2014 LCME site visit and to its present state, which now includes the Learning Communities program, the Office of Service Learning and a formal Preparation for Residency course in the students’ fourth year.

“The process of going through LCME re-accreditation gives us opportunities to not only address challenges we have as a medical school, but to also formalize and grow areas where are strengths are,” Hoesley said. “For example, service learning had been happening in the medical school for years before we established it as a more formal part of the curriculum. After we charged Dr. Caroline Harada as the assistant dean for Community-Engaged Scholarship in 2015, service learning has become a part of every student’s medical school experience. The Office of Service Learning has also grown to include support for student service organization and programs like the Health Equity Scholars and our partnership with the Albert Schweitzer Fellowship.”

Changes to the clinical curriculum stemming from LCME efforts include the establishment of the Montgomery Regional Medical Campus, which opened to its first class of third- and fourth-year students in 2014, and the formalization of the Primary Care Track, which was piloted as a longitudinal integrated curriculum on the Tuscaloosa campus and was formally approved by the LCME in 2017.

High-level changes outside curriculum and the learning environment have been brought forth though accreditation, including the creation of the school’s Office for Diversity & Inclusion, which provided better integration for diversity and inclusion efforts in student affairs, recruitment for faculty and trainees, and continued development of pipeline programs.

“One thing I think we do well in our medical school is understanding the LCME standards, anticipating where changes to the standards might occur and adapting to changes we need to continue evolving as a medical school,” Hoesley said.

In advance of the UAB Heersink School of Medicine’s virtual accreditation site visit April 11-13, we’re sharing how LCME accreditation has shaped the medical school. In Part 2 of the LCME series, Self-Study Task Force co-chairs Irfan Asif, M.D., and Lanita Carter, Ph.D., share what we learned about ourselves as a school during preparations for the 2022 visit.