UAB, University of Cape Town form international partnership to advance kidney transplant capabilities

UAB, University of Cape Town form international partnership to advance kidney transplant capabilities

South African surgeon Elmi Muller pioneered HIV-positive kidney transplants using deceased HIV-positive donors at Groote Schuur Hospital at the University of Cape Town in 2007. It was an achievement that University of Alabama at Birmingham transplant surgeon Jayme Locke, M.D., says paved the way for the HIV Organ Policy Equity Act to be passed by Congress and signed into law here in the United States in 2013.

In fact, Locke says Muller helped the UAB School of Medicine’s Division of Transplantation put the protocols in place at UAB Hospital that enabled Locke and Department of Surgery surgeons to perform the Deep South’s first HIV-positive kidney transplant from an HIV-positive deceased donor in 2016.

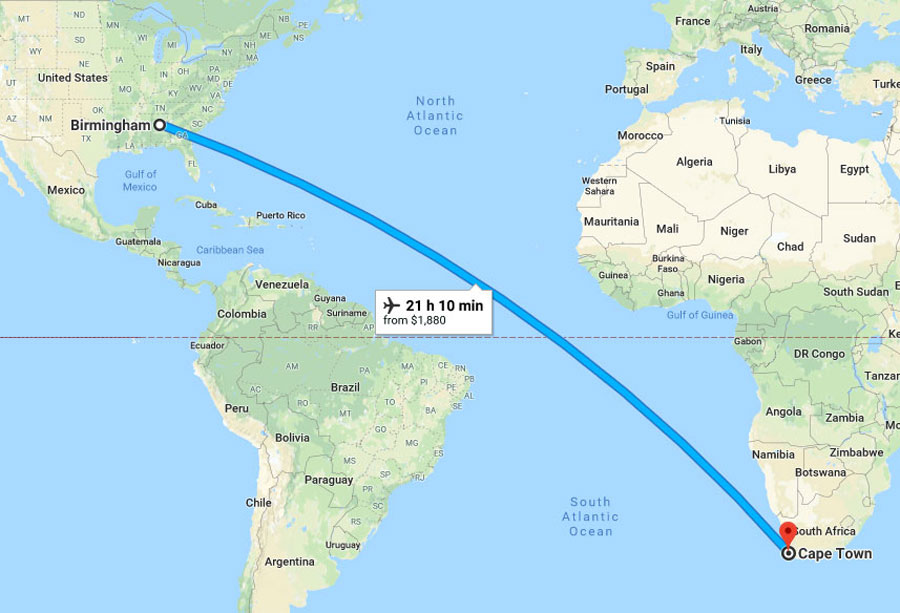

Transplant nurses Katie Stegner, left, and Sara Macedon, center, and transplant surgeon Jayme Locke are in South Africa to help the University of Cape Town's Groote Schurr Hospital implement a paired exchange transplant program, similar to the one that has fueled the success of the UAB Kidney Chain. Since then, Locke has traveled to Groote Schuur as part of her James IV fellowship honor to share protocols with Muller for transplanting highly sensitized and ABO-incompatible patients. Muller’s team performed the continent’s first ABO-incompatible transplant in 2017 as a result of Locke’s first visit. This week, Locke and UAB nurses Katie Stegner and Sara Macedon are on their way back to Cape Town to again work with Muller to broaden transplant capabilities. The goal this time is to help Groote Schuur set up a paired exchange program modeled after the UAB Kidney Chain, the world’s longest ongoing transplant chain.

Transplant nurses Katie Stegner, left, and Sara Macedon, center, and transplant surgeon Jayme Locke are in South Africa to help the University of Cape Town's Groote Schurr Hospital implement a paired exchange transplant program, similar to the one that has fueled the success of the UAB Kidney Chain. Since then, Locke has traveled to Groote Schuur as part of her James IV fellowship honor to share protocols with Muller for transplanting highly sensitized and ABO-incompatible patients. Muller’s team performed the continent’s first ABO-incompatible transplant in 2017 as a result of Locke’s first visit. This week, Locke and UAB nurses Katie Stegner and Sara Macedon are on their way back to Cape Town to again work with Muller to broaden transplant capabilities. The goal this time is to help Groote Schuur set up a paired exchange program modeled after the UAB Kidney Chain, the world’s longest ongoing transplant chain.

“The previously established programs and this new initiative will help us be able to offer more people transplants and to use more of the available living donors here in South Africa,” Muller said. “It also has a huge potential for collaborative research in the future. We are really looking forward to getting this going.”

Locke says the international collaboration efforts between UAB and Groote Schuur have represented a tremendous opportunity for the two groups to answer transplant questions they previously couldn’t while isolated in their own countries. In fact, these efforts and the resulting strategic partnership between UAB and the University of Cape Town have provided the foundation for ground-breaking research in the areas of live-donor transplantation and transplantation of HIV-infected end-stage patients being performed in the UAB Transplant Epidemiology and Analytics in Medicine — a research group under the direction of Locke.

“This is a really a fantastic opportunity clinically and research wise for both groups,” Locke said. “Elmi is a pioneer in the transplant field, and the expertise she and her team provided helped us start our HIV-positive deceased-donor transplant program and change the lives of our HIV end-stage renal disease population here in Birmingham and the Southeast. We are hopeful to be able to follow in the footsteps of Dr. Muller by sharing our expertise in highly sensitized and ABO-incompatible protocols and soon paired exchange and, in so doing, make a positive impact in their country too.”

After providing UAB with HIV-positive deceased donor transplant protocols, a SOM surgical team will provide Groote Schuur Hospital with paired exchange transplant training. Fifteen percent of the population in South Africa has chronic kidney disease. However, shortcomings in the law and widespread unfamiliarity about organ donation are contributing to a major shortage of organs for transplant in South Africa. The problem is particularly severe among patients suffering from kidney failure, thousands of whom are turned away from the dialysis units of public hospitals every year.

After providing UAB with HIV-positive deceased donor transplant protocols, a SOM surgical team will provide Groote Schuur Hospital with paired exchange transplant training. Fifteen percent of the population in South Africa has chronic kidney disease. However, shortcomings in the law and widespread unfamiliarity about organ donation are contributing to a major shortage of organs for transplant in South Africa. The problem is particularly severe among patients suffering from kidney failure, thousands of whom are turned away from the dialysis units of public hospitals every year.

Kidney failure is becoming chronic in South Africa, mainly as a result of the growth in diabetes. Without access to dialysis or a kidney transplant, patients with kidney failure face a bleak future.

Realizing a transplant is often difficult for a variety of reasons. There is no national registry for organ donation. The wishes of a person who wants his or her organs to be donated after death can be overridden by family members because there is no precedent in South African law to ensure that the rights of donors are respected. Another obstacle to transplant is that patients must have a compatible family member donate a kidney in order to participate in a living-donor transplant. Otherwise, the patient has to wait for a deceased donor, which could take years.

Locke says implementing these new transplant techniques will bring greater awareness in South Africa and, hopefully, help them be able to bring a more positive outlook to transplants, ultimately meaning more people receive the opportunity.

“Part of what we will have to work on is overcoming these things so paired exchange could occur, because in a paired-exchange setting, you’re not giving to someone that you know,” Locke said. “For right now, without that option, anybody who has an incompatible living donor can’t achieve transplant. They have to wait for a deceased donor to become available. In that setting, therapies like desensitization to overcome blood group or tissue incompatibility become very important as a means to expanding transplant. That’s what we’ve been working on right now so they can have an immediate need addressed while we work on the long-term goal of creating a paired-exchange — and hopefully at some point a national registry — program for them.”

“I think collaboration works best if people know each other well, and I think we have established a relationship with Jayme now that is really strong and will have huge impact in the future,” Muller said. “The Cape Town team know her, so when I advertise her talks and workshops, everyone is excited, because she spoke so well last time and she is such a nice person. She also has a great sense for people, so when she comes to our centre, it feels like she is one of us rather than someone who is coming to advise us. This is really important as people in the developing world might feel uncomfortable in some of these relationships. We really enjoy having her here and also look forward to have some more members of her team visit us.”