Following the doctor’s orders is often easier said than done. The three ways patients are least likely to comply with a treatment plan are likely not surprising to anyone who has been prescribed a drug or regimen:

- Failure to fill the prescription in the first place.

- Failure to take the prescribed dose regularly.

- Failure to take the prescription to its completion.

View the talks:

|

Michael Stirratt, Ph.D., program chief in the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Division of AIDS Research, spoke of these three most frequently observed failures at a conference on treatment adherence held at the University of Alabama at Birmingham on Feb. 26 titled “Understanding and improving treatment adherence: An interdisciplinary approach.”

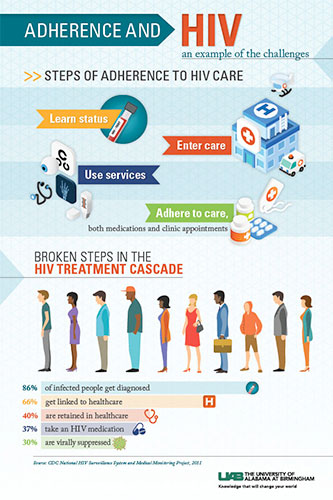

For five years, Stirratt has been co-chair of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Adherence Network, a consortium that aims to strengthen and advance adherence research. Adherence is not only taking drugs as prescribed, but also engaging chronically ill patients in their own health care, he said. Stirratt discussed behavior-change theories and ecologic approaches to adherence support, and noted that the determinants to improving adherence are multilevel, including factors related to the health system, the individual patient, and his or her condition, therapy, and socioeconomic conditions.

Kenneth Saag, M.D., M.Sc., Smita Bhatia, M.D., MPH, and Michael Mugavero, M.D., M.H.Sc., hosted the conference featuring national experts, covering a topic that has challenged clinicians for decades — gaps in treatment adherence.

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

“At the core of this, we’re getting at efficacy, not just seeing patients in a volume-based health care community,” Selwyn Vickers, M.D., senior vice president and dean of the UAB School of Medicine said in his conference welcome. “It’s learning how to have an impact that is truly helpful for our patients.”

The concept for the conference stemmed from one of four multi-investigator grants funded by the UAB School of Medicine as part of the AMC21 reload. Each grantee uses the awarded funds to create a cohesive, interdisciplinary team that will compete for long-term extramural support for a multi-principal investigator grant.

The conference goals, Saag said, were to identify hot topics and key research priorities around treatment adherence, and to foster collaborations toward this research.

Black box

Rivet Amico, Ph.D., School of Public Health, University of Michigan, highlighted the “black box” that persists between designed intervention strategies meant to improve adherence, and the resulting health outcome indicators. Her talk focused on conceptual models and behavioral frameworks to unpack that box. Amico’s research focuses on adherence to antiretroviral medications.

“If your outcomes are not ideal and optimal, we are very concerned about impacting the factors that lead to those outcomes,” Amico said. “In HIV infections, 70 percent of the outcomes are not optimal, and since HIV is an infectious disease, that leads to both individual and public health consequences. To improve outcomes, we need to look at behavior. To impact behavior, we need to look at factors that influence behavior.”

She described several models that provide parsimonious methods to influence behavior, including the health belief model, the information-motivation-behavioral skills model, and the socioecological model. She also talked about how to present models in grants, proposals and talks.

In “Adherence — you can’t improve what you can’t measure,” Jeffrey Curtis, M.D., M.S., MPH, a UAB professor of medicine in the Division of Clinical Immunology and Rheumatology, talked about the use of large databases for adherence research. The need for improvements, he said, is seen in chronic, asymptomatic diseases, for patients taking drugs like beta-blockers, statins, calcium channel blockers and oral diabetic agents.

Curtis reviewed data sources used to measure how well patients are taking their medications, including new technologies like ingestible biosensors that “talk” to a data device worn by a patient, and then to a HIPAA-compliant cloud-based server. He also described a patient-activated learning system he is developing to let patients fill in their own knowledge gaps.

Elizabeth McQuaid, Ph.D., ABPP, research professor of psychiatry, human behavior and pediatrics, Alpert Medical School, Brown University, spoke about cultural issues and health care disparities among racial and ethnic groups influencing therapeutic adherence, specifically related to pediatric asthma. She also highlighted both individual and family characteristics that influence pediatric outcomes.

Funding opportunities

Two speakers presented information on federal funding opportunities for adherence research, representing the National Institutes of Health and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI).

Breakout moderators were:

|

While the conference featured a number of technological approaches to improving adherence, including mobile health technologies such as microchips in pills and glow-cap drug bottles to signal the time for taking medication, Stirratt said sometimes the simplest approaches can yield the greatest results. For example, one study demonstrated that eliminating co-payments for cardiovascular disease patients improved adherence and lowered health care disparities. Another study implemented a weekly text message to HIV patients in Kenya, asking, “How are you?” The patients were told to answer either “fine” or “problem,” and if they sent the latter, they were called by a health care worker. These weekly messages, and the interceding calls, resulted in higher adherence and higher levels of viral suppression for the patients.

Penny Mohr, M.A., senior program officer for improving health care systems at PCORI described the institutes’s patient-centered perspective on adherence research, and she said the PCORI portfolio includes 72 studies where adherence is a primary or secondary focus.

“PCORI is a new form of clinical effectiveness research,” she said. “It considers the patients’ needs, and the preferences and outcomes that matter to patients.”

What happens next

White papers are under development from the conference proceedings for submission as a journal supplement comprising a synthesis of expert opinions addressing four primary therapeutic adherence topics: Behavioral Models and Interventions, Health Communications, Disparities, and Pharmacoepidemiology/Measurement. They will include background topical summaries provided by the conference didactic lectures, thematic research ideas, and hot topics identified by the interactive breakout group discussions and subsequently prioritized by the post-conference qualitative conjoint analysis.

The AMC21 reload grant has a follow-up conference planned for spring 2017, to address navigating therapeutic adherence across disciplines and complex comorbid conditions.