Paige Tatum and son, Wells, 3, along with Catherine Aultman and son, Steyr, 5 months, are patients at UAB's Tuberous Sclerosis Clinic. Photos contributed by Tatum and Aultman families.In 2022, Paige and Baylor Tatum, along with their sons Wells, 3, and Walker, 2, traveled to Birmingham from Mobile a total of 15 times. In 2023, they visited around eight times. And by March of this year alone, they will have spent about four to five weeks in The Magic City. Their visit specifically takes them to the UAB Tuberous Sclerosis (TSC) Clinic at UAB.

Paige Tatum and son, Wells, 3, along with Catherine Aultman and son, Steyr, 5 months, are patients at UAB's Tuberous Sclerosis Clinic. Photos contributed by Tatum and Aultman families.In 2022, Paige and Baylor Tatum, along with their sons Wells, 3, and Walker, 2, traveled to Birmingham from Mobile a total of 15 times. In 2023, they visited around eight times. And by March of this year alone, they will have spent about four to five weeks in The Magic City. Their visit specifically takes them to the UAB Tuberous Sclerosis (TSC) Clinic at UAB.

“To a certain degree, it’s like going to our second home,” said Baylor Tatum. “It’s become so familiar.”

Both Paige and her son, Wells, are patients at the UAB TSC Clinic, which was established in 2007 by Martina Bebin, M.D., M.P.A., professor in UAB’s Department of Neurology, and Bruce Korf, M.D., Ph.D, associate director of UAB’s Hugh Kaul Precision Medicine Institute.

Tuberous sclerosis (TSC) is a genetic disease that can affect multiple bodily systems—most commonly, the central nervous system—by causing benign tumors to form in a number of vital organs. Symptoms can include seizures, developmental delays, autism, hypertension, kidney disease, and more.

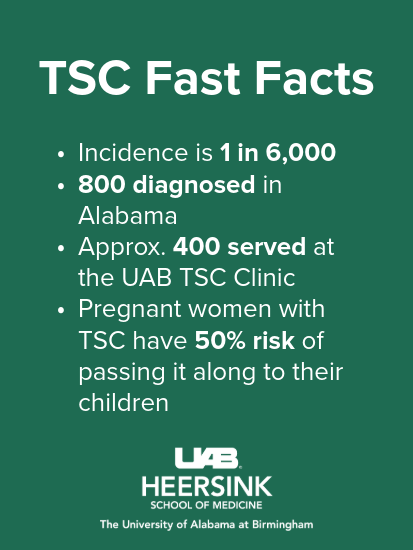

The incidence of TSC is about 1 in 6,000, with about 800 people in Alabama estimated to have the disease. Of those 800, approximately 400 find care and support at the UAB clinic.

The incidence of TSC is about 1 in 6,000, with about 800 people in Alabama estimated to have the disease. Of those 800, approximately 400 find care and support at the UAB clinic.

Bebin explained that the life expectancy for having TSC is the same as the general population.

“But the burden of health issues can vary, but each patient should have a physician familiar with TSC, and follow the TSC specific clinical guidelines to keep you healthy, which is so, so important,” she added. “And that’s really the purpose of the clinic.”

The diagnosis

Wells started having seizures at 3 months old. When Wells was 9 months old, genetic testing at the Tatum family’s local hospital revealed a genetic mutation of his TSC 2 gene, and Wells was diagnosed with tuberous sclerosis.

“And from there, we were able to get connected with Dr. Bebin and get in with the TS clinic,” Baylor explained. “And that’s when we were really able to formulate a plan to figure out next steps and how to control this and even better understand what it was we were dealing with.”

Being that TSC is a genetically inherited disorder, part of those next steps involved testing Paige, Baylor, and Wells’ brother, Walker, for the TSC mutation.

“Mine came back positive for the same gene, which was interesting to know that we have the same genetic mutation,” Paige said.

For Catherine Aultman, who has been a patient at UAB’s TSC Clinic since October 2023, the situation was similar. At 17 weeks pregnant and living in Washington in 2021, an ultrasound revealed Aultman’s daughter had a large heart tumor. Tragically, she passed away at 23 weeks.

“They found out she had TSC, so they did genetic testing on myself, and I was found to have it,” Aultman said. “I didn’t really have much direction up there in Washington State of where to go or what to do after that.”

A cross-country move in 2022 led Aultman and her husband to North Alabama and eventually, Huntsville Hospital. This was where her now 5-month-old son, Steyr, was diagnosed with TSC in utero around 31 weeks. From there, she was directed to Bebin and the UAB TSC Clinic.

“She knows this disease, she knows how important it is to start regular monitoring for seizures at his young age, and she had her team move at light speed,” Aultman said.

Multi-generational care

One of the draws of UAB’s TSC Clinic, which is one of only 10 in the nation that has earned a TSC Center of Excellence designation from the TSC Alliance, is the fact that it caters to patients spanning from infancy to adulthood.

Bebin and her team, which includes a roster of both pediatric and adult specialists, coordinate with primary care physicians, offer telehealth if patients are out of town, and generally work together to ensure patient care is optimal—for all members of the family.

“I have some families where I take care of the three generations,” Bebin said. “And that’s the benefit—they know who they’re coming to. We’ve seen them grow up, and it makes things easier.”

Routine care can involve MRI imaging, EEGs, blood tests, monitoring of lung function and kidneys, and more. But beyond the technical care, the clinic seeks to empower its patients with knowledge about the disease and how to address it.

“We kind of anchor them,” Bebin said “We are your resource. We will do all the things that are necessary. It’s one phone call to have everything taken care of.”

According to Bebin, the research surrounding TSC at UAB has led the clinic to be able to diagnose more and more infants as early in life as possible, ideally before they are even born. From that point on, the babies, as well as any additional family members who may be diagnosed, are supported by the TSC Clinic—for life.

“They’ve always been so responsive and quick to make things happen, and we’re never just sitting around and wondering,” Paige said. “We’ve always felt so taken care of, and not just Wells, but us as parents.”

A support team for life

Paige and Baylor Tatum along with sons Walker, 2, and Wells, 3. Photo contributed by Tatum family. Aultman and Steyr travel to the clinic about every six weeks for care. Steyr is enrolled in a clinical trial, called the STEPS program, which is studying how to find a way to prevent seizures beginning with infants. Aultman touted the clinic for making her life more navigable while monitoring both her and her son’s TSC.

Paige and Baylor Tatum along with sons Walker, 2, and Wells, 3. Photo contributed by Tatum family. Aultman and Steyr travel to the clinic about every six weeks for care. Steyr is enrolled in a clinical trial, called the STEPS program, which is studying how to find a way to prevent seizures beginning with infants. Aultman touted the clinic for making her life more navigable while monitoring both her and her son’s TSC.

“It is a lot of stress off my shoulders,” Aultman said. “In Washington State, I had no direction. I didn’t know what to do, and now I do, and I have that confidence that I have a team I can rely on to help me take the best care of my son and myself.”

As research on TSC advances at the UAB clinic and beyond, both families expressed they are hopeful that these advancements will continue to create an improved quality of life for people living with the disease.

And having found peace of mind has already contributed to that goal.

“As a parent, your biggest fear is – am I doing enough, am I doing everything I can?” Baylor said. “And being able to look at his team of doctors and surgeons and know that he’s in the very, very best hands—that’s all that you can ask for.”

For more information about TSC, visit tscalliance.org.