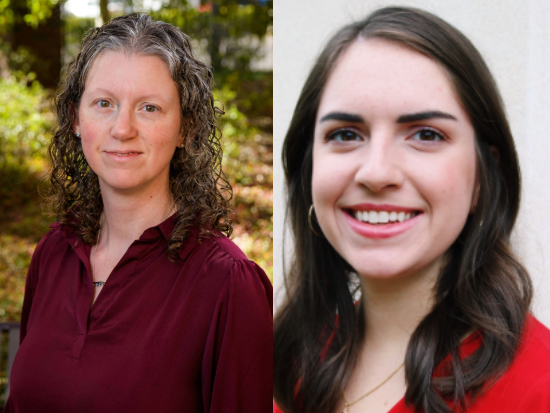

November is National Epilepsy Awareness Month, and the Epilepsy Genomics Clinic at UAB is reimagining how to treat epilepsy in adults with an innovative approach. Ashley Thomas, M.D., director of the clinic and associate professor in the Department of Neurology, and Elizabeth Rothrock, M.S., LCGC, genetic counselor of the clinic and in the Department of Genetics, started the clinic roughly five years ago, and it has expanded since.

November is National Epilepsy Awareness Month, and the Epilepsy Genomics Clinic at UAB is reimagining how to treat epilepsy in adults with an innovative approach. Ashley Thomas, M.D., director of the clinic and associate professor in the Department of Neurology, and Elizabeth Rothrock, M.S., LCGC, genetic counselor of the clinic and in the Department of Genetics, started the clinic roughly five years ago, and it has expanded since.

Literature suggests that up to 40 percent of patients with epilepsy will have a genetic reason for their diagnosis, and genetic testing has primarily been done in pediatrics. With this in mind, the clinic has incorporated genetic testing to better understand how to treat adults with epilepsy.

The clinic is a state-of-the-art, high-volume surgical center. It is the only center in the southeast that has an integrated Epilepsy Genomics Clinic and one of only a handful in the country.

“We are finding genetic reasons for our patients' epilepsy when they have been searching for answers, often for years,” Thomas said. “It is very rewarding to be able to provide answers for patients and their families. For some patients, we can make recommendations for changes in treatment that can improve seizure control or for monitoring other medical conditions. This is a precision medicine approach to the treatment of epilepsy.”

With this approach, the clinic has found patients where making a genetic diagnosis has changed their prescription and care management, significantly improving their quality of life. While using genetic testing for epilepsy is not necessarily new, the novelty comes in using it for adult patients.

When Adithyaa Chidambaram moved to Birmingham in 2022, he and his family had been searching for answers to his epileptic seizers his whole life. They became connected with a doctor at the UAB Epilepsy Center, Lawrence Ver Hoef, M.D., and instantly felt comfortable with him. Adithyaa was tested in the clinic, and they found a genetic abnormality. Only about 200 people in the world are diagnosed with this genetic abnormality.

“It was a bittersweet feeling getting those results, but I’d have to say it was more sweet than bitter,” said Adithyaa’s father, Balan. “After 20 years of constant fighting and battle, it was a huge sense of relief to now have a name for what has been going on. We now have a community that we can talk to and share thoughts and ideas with.”

After his diagnosis, Adithyaa was prescribed a medication that is most commonly used for multiple sclerosis. He has now been using this prescription for about six months, and his seizures have significantly decreased.

“This clinic has provided diagnoses for a lot of folks who ‘missed the boat’ on genetic testing as children, so it’s great to be able to give families some answers,” Rothrock said.

The clinic is primarily accepting patients with an epilepsy diagnosis and no other preexisting conditions.