Connie Pittman was an extraordinarily remarkable and wonderful person. She had a brilliant mind, a great capacity for learning, a fierce work ethic, a great capacity for friendship and for accepting people as she found them – except for her children, Clinton and John, whom she pushed to succeed. She loved Jim dearly. They married in 1955 and moved to Birmingham in 1956.

Connie Pittman was an extraordinarily remarkable and wonderful person. She had a brilliant mind, a great capacity for learning, a fierce work ethic, a great capacity for friendship and for accepting people as she found them – except for her children, Clinton and John, whom she pushed to succeed. She loved Jim dearly. They married in 1955 and moved to Birmingham in 1956.

Connie and Jim lived in our neighborhood on Shades Mountain. Our children attended Highlands Day School, so we took turns taking our children back and forth to school. My children felt very close to Connie and totally trusted her as a surrogate mom.

Connie was born in Nanjing and grew up in Beijing, where she lived with her parents and two brothers. Her father was a dean at Tsinghua University, and her mother was librarian there. Tsinghua was built by the boxer Rebellion reparations money returned by the United States under President Theodore Roosevelt to the Chinese government. Tsinghua is sometimes referred to these days at the MIT of China. Connie’s mother and father had both been educated in the United States on Boxer Scholarships – she at Wellesley College and he at the University of Chicago and Columbia University. The family spoke English during their evening meals.

Then came World War II. As the war progressed, it became evident that the family and the school need to be moved. They fled to Kunming, near the end of the Burma Road, on a bus, a very long way across chaotic and underdeveloped China. Connie told me that, at first, they thought they could exist under Japanese rule. Her aunt had talked the Japanese soldiers into respecting her and behaving well in her presence. Then the soldiers killed her aunt and stuffed her body down a well -- horrifying to contemplate.

Then came World War II. As the war progressed, it became evident that the family and the school need to be moved. They fled to Kunming, near the end of the Burma Road, on a bus, a very long way across chaotic and underdeveloped China. Connie told me that, at first, they thought they could exist under Japanese rule. Her aunt had talked the Japanese soldiers into respecting her and behaving well in her presence. Then the soldiers killed her aunt and stuffed her body down a well -- horrifying to contemplate.

At 16, Connie began to volunteer with Friends Ambulance Unit: The China Convoy, a group of conscientious objectors from the British Empire who provided medical aid to civilians and military alike. She recalled dripping ether for limb amputations. Connie kept up with the group, and she and Jim went on a trip back to China with some of the in 1996. Over the 50 years, many had become professors, physicians, and eminent scientists from Canada as well as the United Kingdom. At the beginning of the war, these men were sent to Burma, along with all their equipment, which they were to take over the Burma Road to China. Finding that their trucks were too wide for the Burma Road bridges, the men sold them and managed to build or fabricate narrower trucks fueled by charcoal.

After deciding to become a physician, Connie came to the United States in 1946 on a troop ship – but only after a suitable chaperone had been identified. I asked her how her family managed to send her, given the loss of property and money because of the war. She told me that her father sold a ring to finance the journey. She was received by friends her mother had made while in school in the United States.

The China Convoy on the Burma RoadShe first attended Walnut Hill School in Natick, Mass., then Wellesley College, and then Harvard Medical School, where she met Jim. More than 60 years later, a Wellesley classmate remembered with admiration that Connie received other very good offers but “held out for Harvard.” Connie told me that during this time she felt that, not only for her parents, but all of China was watching her and expecting her to do well. And she did, Fifty years after her graduation from Walnut Hill, Connie and one other graduate were recipients of the Non Nobis Solem Award (Not for Ourselves Alone) as outstanding graduates of the school for the 20th Century. The other recipient was an astronaut.

The China Convoy on the Burma RoadShe first attended Walnut Hill School in Natick, Mass., then Wellesley College, and then Harvard Medical School, where she met Jim. More than 60 years later, a Wellesley classmate remembered with admiration that Connie received other very good offers but “held out for Harvard.” Connie told me that during this time she felt that, not only for her parents, but all of China was watching her and expecting her to do well. And she did, Fifty years after her graduation from Walnut Hill, Connie and one other graduate were recipients of the Non Nobis Solem Award (Not for Ourselves Alone) as outstanding graduates of the school for the 20th Century. The other recipient was an astronaut.

Connie’s parents planned to come to Boston to visit her but decided to wait one more year so they could watch her graduate from Wellesley. When that time came, China did not allow travel, so Connie never saw her mother after the farewell in 1946, and did not see her father again until after President Nixon opened China for American travel in 1972. Her father had been blinded by mistreatment during the Red Guard period and was very infirm; her mother had died. Connie made arrangements to have her surviving brother, Ming-Hong Shen, and his wife and children join her in Birmingham. They arrived in 1980, and her brother had a fine career in physics at UAB. Connie’s nephew was 12 at the time of his arrival in Alabama, and he quickly became fluent in English. She was very proud of him for excelling at school while learning English. He received a scholarship to Vanderbilt, where he excelled. He is now an engineer in Huntsville.

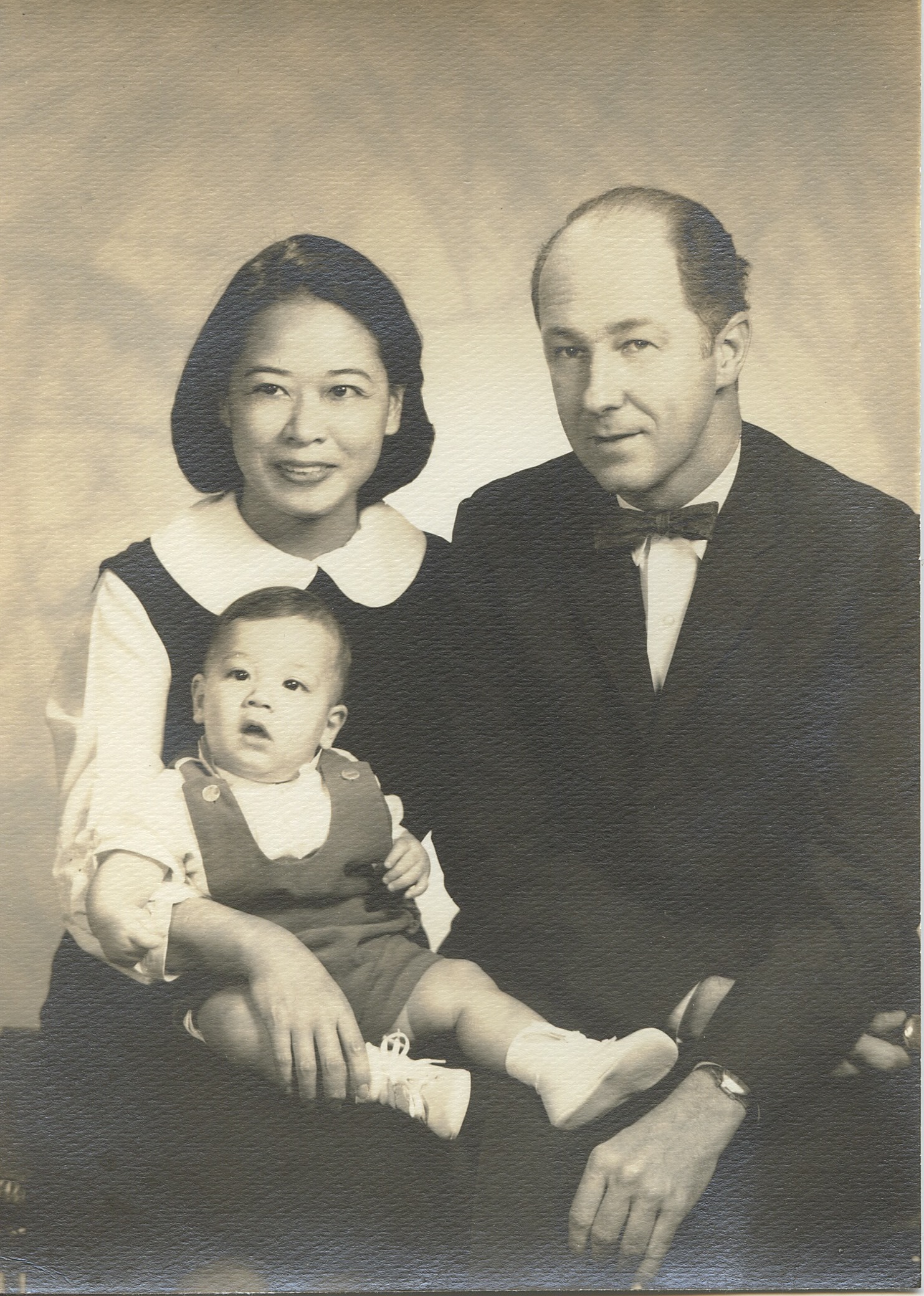

Connie and Jim Pittman with Clinton, the first of their two sonsJudy Swatland and Connie became good friends at Wellesley. The friendship extended to Judy’s parents, whom Connie always called her American family. Mr. Swatland’s name was Donald Clinton Swatland; Clinton Pittman is named for him. The Swatlands hosted Connie’s wedding to Jim, whose parents did not approve of the marriage and did not attend. Connie, in her usual matter-of-fact way, seemed to understand their difficulty in accepting her. She persisted in being herself and continued to pay them the utmost respect. Jim once made a joke of all this when, introducing their son Clinton to the Rotary Club, he said, “Clinton is the result of a mixed marriage – his father is Rotarian and his mother belongs to the Kiwanis Club.”

Connie and Jim Pittman with Clinton, the first of their two sonsJudy Swatland and Connie became good friends at Wellesley. The friendship extended to Judy’s parents, whom Connie always called her American family. Mr. Swatland’s name was Donald Clinton Swatland; Clinton Pittman is named for him. The Swatlands hosted Connie’s wedding to Jim, whose parents did not approve of the marriage and did not attend. Connie, in her usual matter-of-fact way, seemed to understand their difficulty in accepting her. She persisted in being herself and continued to pay them the utmost respect. Jim once made a joke of all this when, introducing their son Clinton to the Rotary Club, he said, “Clinton is the result of a mixed marriage – his father is Rotarian and his mother belongs to the Kiwanis Club.”

Connie was, in fact, a stellar member of the Kiwanis Club. The Kiwanians took up the challenge of fighting iodine deficiency disorders on a worldwide scale and raised $70 million for that cause in the 1990s. Connie was a perfect leader in effort; not only was her training and knowledge as an endocrinologist invaluable, but her knowledge of languages and her diplomatic skills made her highly effective. She worked diligently on this project for many years, logging thousands of miles as she traveled the world. She attended meetings of producers of table salt and worked to convince them to add iodine to their products. When Connie gave the Reynolds Historical Lecture at UAB in 1993, her topic was iodine deficiency. She made the subject come alive. I remember one of her most compelling pictures was of a medieval painting of a Madonna and child in which the Madonna has a goiter and the child was deformed. In our times, much of the IDD is found in Asia, so Connie’s knowledge was especially important.

In 1996, Connie and Jim visited China in the company of others who had served in the Friends Ambulance Unit: The China Convoy. They searched unsuccessfully for Ssu-Kung-Li, the site of the headquarters building where she had worked alongside other volunteers. “I now realize that Ssu Kung Li Pan will always be there,” she later wrote. “We can turn off at the four-and-a-half-kilometer marker whenever we wish, to return to that place in our hearts where we will remain forever handsome and young, gay and spirited, where we will answer the call of our conscience, and give comfort and aid to China when she needs us most.”

A lifelong resident of Birmingham, Mary Carolyn Gibbs Boothby Cleveland was a friend of Connie Pittman’s for more than 40 years. Formerly a landscape designer and active community volunteer, she is currently chairman of Boothby Realty, Inc.

A lifelong resident of Birmingham, Mary Carolyn Gibbs Boothby Cleveland was a friend of Connie Pittman’s for more than 40 years. Formerly a landscape designer and active community volunteer, she is currently chairman of Boothby Realty, Inc.