The number of people coping with a memory disorder or caring for a loved one with a memory disorder is rising.Shortly after being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2011, singer Glen Campbell recorded a song called “Ghost on the Canvas.” The song begins with the line, “I know a place between life and death for you and me.”

The number of people coping with a memory disorder or caring for a loved one with a memory disorder is rising.Shortly after being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2011, singer Glen Campbell recorded a song called “Ghost on the Canvas.” The song begins with the line, “I know a place between life and death for you and me.”

An existence in limbo is a daily reality for many of the 5.5 million people in the U.S. currently living with Alzheimer’s disease or another form of dementia. It also often accurately describes the agonizing circumstances facing the more than 15 million Americans who provide care for family members and loved ones suffering from memory disorders.

“It just takes over your life,” Kim Campbell, Glen Campbell’s wife of 34 years, said in an interview with The Tennessean a few months before Campbell’s death from Alzheimer’s this past August. “They are losing their identity because they can’t remember who they are, but as a caregiver you are losing your identity. You have to give up everything you are doing to take care of them.”

UAB researchers are actively working to find treatments and hopefully even a cure for Alzheimer’s and other memory disorders. Until those breakthroughs occur, UAB’s School of Medicine and School of Nursing are teaming up to try to help current patients and especially caregivers deal with this fatal disease that has been referred to as “the long goodbye.”

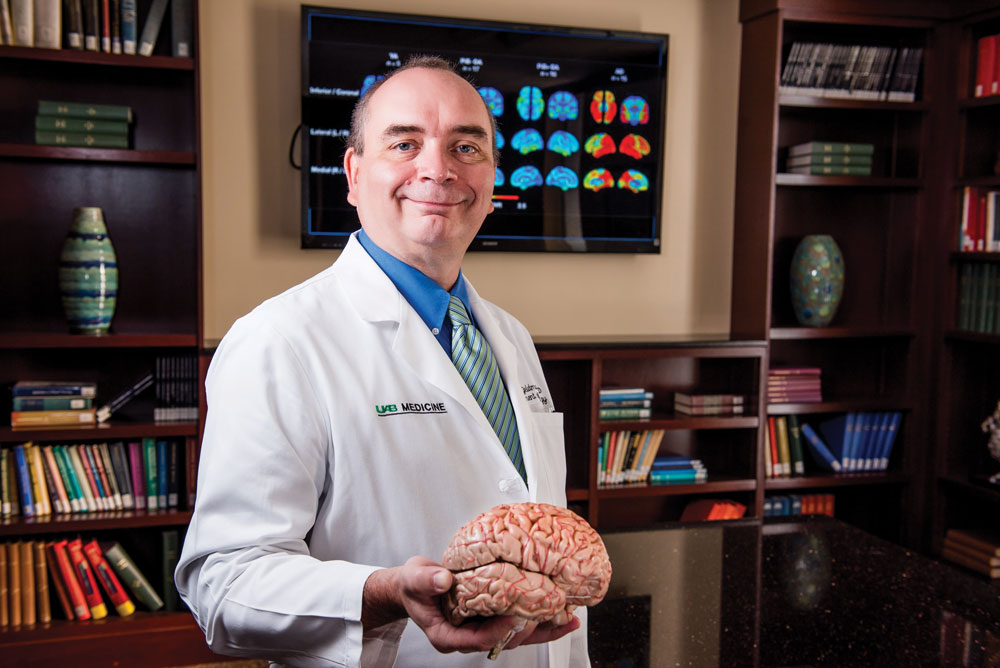

David Geldmacher from the School of Medicine is co-leading efforts to help people with memory disorders and their families cope and preserve quality of life. “Our focus is to try to promote the quality of life in the family as a whole,” says David Geldmacher, M.D., holder of the Warren Family Endowed Chair in Neurology and director of the UAB Division of Memory Disorders and Behavioral Neurology. “There are things we can do for the affected person—prescribe medicines and so forth—but there are also things we can do for the family members and caregivers. Since most people with dementia are cared for in the home environment, our goal is to try to optimize that family’s functioning and quality of life to the greatest extent possible.”

David Geldmacher from the School of Medicine is co-leading efforts to help people with memory disorders and their families cope and preserve quality of life. “Our focus is to try to promote the quality of life in the family as a whole,” says David Geldmacher, M.D., holder of the Warren Family Endowed Chair in Neurology and director of the UAB Division of Memory Disorders and Behavioral Neurology. “There are things we can do for the affected person—prescribe medicines and so forth—but there are also things we can do for the family members and caregivers. Since most people with dementia are cared for in the home environment, our goal is to try to optimize that family’s functioning and quality of life to the greatest extent possible.”

Though Alzheimer’s is the memory disorder that receives the most attention, Geldmacher says there are a number of other diseases and conditions that can cause neurological issues that result in changes to personality and behavior similar to Alzheimer’s. These include Parkinson’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, head injuries, strokes, and even sleep disorders.

“When we use the term dementia, we mean a change in cognition or behavior attributable to brain disease that’s severe enough to interfere with a person’s everyday activities,” Geldmacher says. “So saying ‘dementia’ is like saying ‘headache.’ It’s a generic, overall description of what we observe. But there are many causes of dementia, just like there are many causes for headaches. Dementia is the umbrella term, and specific illnesses like Alzheimer’s disease are the individual spokes.”

A Gathering Storm

Regardless of how the various illnesses are categorized, the overall issue of people in this country suffering from memory disorders is a rapidly growing problem. According to a report released earlier this year by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, death rates from Alzheimer’s rose 55 percent from 1999 to 2014 and nearly 14 million people are expected to be afflicted with the disease in the next 20 to 25 years.

“Meanwhile, we have a smaller cohort of people being left behind to take care of these older adults as they move into dementia,” Geldmacher says. “We also have difficulty attracting doctors and nurses to this field, so we have a growing shortage of specialists with an expertise in this area. Unless we come up with treatments that significantly interrupt the progression of the disease or even prevent its emergence, the public health burden on Medicaid and Medicare and the like will be overwhelming by mid-century.”

Rita Jablonski from the School of Nursing is also co-leading efforts to help patients with memory disorders and their families cope. Rita Jablonski, Ph.D., CRNP, FAAN, FGSA, associate professor with the UAB School of Nursing, is even more emphatic about the problem’s severity. “The dementia crisis is here. It’s not coming; it’s here,” Jablonski says. “Almost $300 billion is expended annually because of this diagnosis, either directly through hospitalization and nursing home care costs or indirectly because family caregivers have to leave the workforce or accept lower-paying positions that enable them to offer care. And that number is only going to go up.”

Rita Jablonski from the School of Nursing is also co-leading efforts to help patients with memory disorders and their families cope. Rita Jablonski, Ph.D., CRNP, FAAN, FGSA, associate professor with the UAB School of Nursing, is even more emphatic about the problem’s severity. “The dementia crisis is here. It’s not coming; it’s here,” Jablonski says. “Almost $300 billion is expended annually because of this diagnosis, either directly through hospitalization and nursing home care costs or indirectly because family caregivers have to leave the workforce or accept lower-paying positions that enable them to offer care. And that number is only going to go up.”

Since the treatment options for patients with memory disorders remain limited, the focus is increasingly turning toward helping caregivers and other family members deal with the disease. Toward that end, Geldmacher says the UAB Memory Disorders Clinic is creating a new position that he calls “a nurse navigator.”

“Families often don’t know where to turn with their questions,” Geldmacher says. “We hope to provide a single focal point for families that we work with that allows them to call in and get referrals to community resources and other education as needed. We could potentially even have group educational sessions, where we can help families understand what they’re facing and the best ways of managing it.”

UAB is also using a $500,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) on a three-year study to see if family members can be taught caregiving strategies through online or phone instruction. The DoD is interested in studying dementia because a large number of aging and younger veterans are experiencing memory-related problems stemming from head injuries sustained during combat. Such telemedicine programs are important since many rural areas do not offer any assistance for these types of patients and their caregivers.

“We know that a head injury is a risk for developing dementia later in life,” Geldmacher says. “And we know that many of the symptoms of people who have experienced repeated brain trauma—such as changes in memory, thinking, and behavior—are very similar to the symptoms that patients with Alzheimer’s disease experience. That’s why the study for both caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease and brain injury aims to find out their similarities and their differences. It looks to see if we can create a telemedicine caregiver coaching program that caters to both.”

As part of the study, Jablonski says she spends an hour each week for a total of six weeks talking with an individual caregiver. They discuss the problems the caregiver is having with the patient, and Jablonski offers advice on how best to solve the issues. For example, patients with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia from traumatic brain injury may resist care efforts from family members, such as taking a bath, taking medicine, practicing routine mouth care, abstaining from alcohol, or going to a medical appointment. When Jablonski and the caregiver talk again a week later, the caregiver will describe what worked well and what didn’t and Jablonski will offer fresh advice based on this feedback.

“This type of interaction is mandatory for family members to become more adept at caregiving,” Jablonski says. “They know their loved one better than anybody. They can take our general strategies and then tailor them to that person’s specific behavior.

“We are logical beings, and logic doesn’t work with dementia. So the way you’ve interacted with them your whole life through logic and reasoning goes out the window with dementia. In fact, a lot of the ways you used to interact with them can now cause behavior triggers that make them upset.”

Jablonski says the most common behavior associated with people with memory disorders is repetition, where the person will ask the same question over and over. “Every five minutes they’ll ask what time it is,” Jablonski says. “Things like that can really wear down family caregivers.”

Jablonski teaches techniques that enable caregivers to try to preempt such repetitive behaviors. If a patient continually asks about the time, she says the caregiver should put a large digital clock in the room and then ask the patient what time it is. “Beating the person to the repetitive question can sometimes move the repetitive train of thought off the track,” Jablonski says. “You can bounce them out of the loop so maybe that behavior lessens.”

On the clinical side, UAB has a group of nurse practitioners who provide longitudinal ongoing care for patients and families facing dementia. Geldmacher points out UAB has the only board-certified cognitive neurologists and nurse practitioners who provide the only outpatient-focused expertise in dementia care in the state. Therefore, it makes sense the School of Medicine and the School of Nursing have formed this partnership to help caregivers navigate this strange and frightening situation.

“Our doctors do a lot of diagnosis, but so much of what happens in the care of the person with dementia is nursing-oriented care, and doctors aren’t really taught that in medical school,” Geldmacher says. “Many people come in wanting to see the doctor because the doctor is going to ‘fix’ the problem. Well, unfortunately for Alzheimer’s disease we know the doctor can’t fix the problem. It’s not going away. That person is going to live with that problem for the rest of their lives.

“How do you live with dementia? That’s what nursing is, the care of the person with the disease. The disease is irrelevant; it’s the person who’s the focus. A lot of people resist transitioning to the nurse practitioner when in fact that health care professional offers the right expertise. The nursing expertise in our group is every bit as important, if not more important, than the physician expertise.”

Prevention & Reduction

With nearly half a million new cases of Alzheimer’s disease diagnosed each year in the U.S.—and an aging baby boomer generation expected to push that figure even higher—it’s clear that efforts to combat the disease will have to do more than treat and support those who are already afflicted. For that reason, clinicians and researchers are increasingly turning their attention toward preventive efforts for Alzheimer’s.

With nearly half a million new cases of Alzheimer’s disease diagnosed each year in the U.S.—and an aging baby boomer generation expected to push that figure even higher—it’s clear that efforts to combat the disease will have to do more than treat and support those who are already afflicted. For that reason, clinicians and researchers are increasingly turning their attention toward preventive efforts for Alzheimer’s.

“The lesson we’re drawing from is the history of cardiovascular disease,” says Geldmacher. “In the 1950s, we didn’t know that someone had heart disease until they had a heart attack. Then we realized there were reversible risk factors and that you can treat heart disease long before a heart attack. The day may come when we can do the same thing with Alzheimer’s by finding the illness before any symptoms appear and intervening to prevent brain disease.”

Geldmacher imagines a future where healthy adults undergo routine screenings as they age that look for the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s in the brain with routine scans or tests in the same way blood tests screen for predictors of heart disease. At UAB, clinical trials involving both healthy people and those with dementia, as well as basic research to uncover the molecular underpinnings of Alzheimer’s disease, are helping bring Geldmacher’s vision to life.

Personalized Advice

Today, screening for Alzheimer’s in healthy adults is, in most primary care settings, limited to a short questionnaire. But for those interested in a more detailed examination of their likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s, UAB runs a first-of-its-kind personalized risk clinic, a reflection of the growing influence of precision medicine. Helmed by Geldmacher, the Alzheimer’s Risk Assessment and Intervention Clinic will—for a fee—perform memory tests, collect family history, and carry out a patient’s baseline MRI scan to integrate into his or her personal dementia risk assessment. If the patient has a heightened risk of Alzheimer’s disease, Geldmacher advises the patient how to decrease that risk.

“There’s a lot of junk information on Alzheimer’s out there,” says Geldmacher. “People can’t always sort out what is valid and what is snake oil. We offer personalized attention. We let them know what they can do and inform them on how certain behaviors affect their risk.”

The Alzheimer’s Risk Clinic medical professionals’ advice is based on a few large studies’ results that followed healthy adults and tracked who developed Alzheimer’s disease. Studies are still needed to determine whether changing risk factors—like diet—actually alter the risk of Alzheimer’s. Additionally, research is needed to uncover new drugs that may prevent the onset of dementia in those most at risk.

Strengthening Defenses

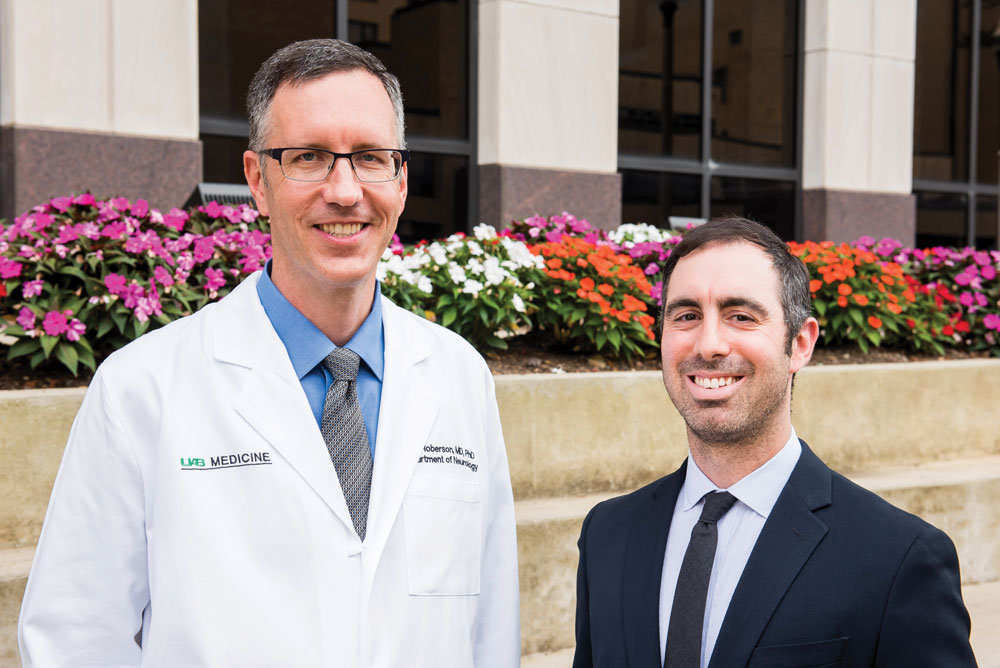

Left to right: Erik Roberson and Jeremy Herskowitz are researching ways to better understand the neurological and neurobiological mechanisms behind the development of Alzheimer's disease.Researchers at UAB and around the country are simultaneously trying to better understand what causes Alzheimer’s at a molecular level and how those underlying changes to the brain can be stopped or reversed. Over the past couple of decades, two proteins—amyloid-beta and tau—have been implicated in the disease’s development. Both proteins are known to accumulate in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s, forming clumps known as amyloid plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles. But when researchers autopsy the brains of healthy people—who died without ever having memory problems—they also see a significant percentage of brains with amyloid plaques and tau tangles.

Left to right: Erik Roberson and Jeremy Herskowitz are researching ways to better understand the neurological and neurobiological mechanisms behind the development of Alzheimer's disease.Researchers at UAB and around the country are simultaneously trying to better understand what causes Alzheimer’s at a molecular level and how those underlying changes to the brain can be stopped or reversed. Over the past couple of decades, two proteins—amyloid-beta and tau—have been implicated in the disease’s development. Both proteins are known to accumulate in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s, forming clumps known as amyloid plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles. But when researchers autopsy the brains of healthy people—who died without ever having memory problems—they also see a significant percentage of brains with amyloid plaques and tau tangles.

According to Jeremy Herskowitz, Ph.D., an assistant professor of neurology and neurobiology and the Patsy W. and Charles A. Collat Scholar of Neuroscience, “There are large numbers of individuals from between the ages of 60 and 100 who have Alzheimer’s pathology but no dementia.” Herskowitz is studying what differentiates people who have amyloid-beta and tau pathology in their brains but do not develop dementia from those who have dementia. His lab recently used cutting-edge microscopy techniques to examine brains of elderly individuals who had died with and without Alzheimer’s diagnoses. They found that the synapses (connections between nerve cells) in people who avoided Alzheimer’s looked completely different—they were longer and more extensive.

“Now we understand how some individuals can withstand dementia despite harboring the pathology in their brains,” he says. “We will focus on drugs to remodel the synapses in patients prone to Alzheimer’s to slow down the development of dementia.” Herskowitz is now pursuing a class of drug that may boost synapses even when amyloid and tau accumulate.

“The research field is beginning to accept the idea that an Alzheimer’s therapy will attack the disease from all angles: reducing tau and amyloid, curbing neuroinflammation, and boosting synapses,” Herskowitz says.

Erik Roberson, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of neurology and neurobiology, the Patsy W. and Charles A. Collat Professor of Neuroscience, and director of the UAB Alzheimer’s Disease Center, is working on a new twist on of those approaches: attempting to disrupt the effects of tau on the brain. In healthy brain cells, tau proteins help form tracks that transport materials throughout the cells. But when tau proteins accumulate into tangles—as they do in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s—transportation goes awry, cells die, and areas of the brain become hyperexcitable.

“In mice, we can fix this hyperexcitability by knocking out their tau genes,” says Roberson. “But we can’t do that in people.” Instead, Roberson’s lab is working on developing drugs that keep tau from interacting with other proteins that, when they team up, may cause the hyperexcitability. Like Herskowitz’s plan to change synapses that could block the disease even in the face of amyloid plaques and tau tangles, Roberson is hoping that thwarting tau’s interactions may stop Alzheimer’s without changing amyloid or tau levels.

Clinical Questions

Through his role as chair of the UAB McKnight Brain Institute, Ronald Lazar is working with researchers like Herskowitz and Roberson to connect memory disorders research.Through his role at the Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Roberson is also zooming out from the molecular details of dementia to answer some broader questions about who gets Alzheimer’s and why. The center is about to start recruiting patients with and without Alzheimer’s to study how health disparities in Alabama contribute to rates of the disease. African-Americans are at a significant higher risk for Alzheimer’s, and many other risk factors for dementia—from cardiovascular disease to obesity—are present at higher than average rates in Alabama. “We really need to understand why some people have higher risks and what’s unique about them that should guide the way we approach treatment for them,” says Roberson.

Through his role as chair of the UAB McKnight Brain Institute, Ronald Lazar is working with researchers like Herskowitz and Roberson to connect memory disorders research.Through his role at the Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Roberson is also zooming out from the molecular details of dementia to answer some broader questions about who gets Alzheimer’s and why. The center is about to start recruiting patients with and without Alzheimer’s to study how health disparities in Alabama contribute to rates of the disease. African-Americans are at a significant higher risk for Alzheimer’s, and many other risk factors for dementia—from cardiovascular disease to obesity—are present at higher than average rates in Alabama. “We really need to understand why some people have higher risks and what’s unique about them that should guide the way we approach treatment for them,” says Roberson.

It is a question that is also at the heart of research being conducted at the UAB Evelyn F. McKnight Brain Institute, which welcomed Ronald Lazar, Ph.D., the Evelyn F. McKnight Endowed Chair for Learning Memory in Aging in the Department of Neurology, as its new chair this summer.

“We want to take UAB’s strengths in both research and clinical medicine and build new relationships between basic scientists and clinical scientists to study age-related memory decline and cognitive decline, and discover how to create resiliency and recovery,” says Lazar. “There are a lot of principles that have emerged out of basic science, and there are wonderful cellular and animal models of Alzheimer’s. Our challenge is to bring this work forward into the human space.”

The institute—one of four McKnight Brain Institutes in the country—was launched at UAB in 2004, and Lazar is already planning new initiatives that include pilot grants to facilitate interdisciplinary work.

Through collaborations with the other McKnight sites, UAB associate professor of neurobiology Kristina Visscher, Ph.D., is involved in one such interdisciplinary project that aims to define the healthy aging brain.

Kristina Visscher works on imaging studies that seek to define and characterize a healthy aging brain. “There are theories out there that say Alzheimer’s is an acceleration of brain aging,” explains Visscher, co-director of the Civitan International Neuroimaging Laboratory. “But the problem is that we don’t actually understand what a healthy aging brain means.”

Kristina Visscher works on imaging studies that seek to define and characterize a healthy aging brain. “There are theories out there that say Alzheimer’s is an acceleration of brain aging,” explains Visscher, co-director of the Civitan International Neuroimaging Laboratory. “But the problem is that we don’t actually understand what a healthy aging brain means.”

Visscher and researchers at the McKnight Institutes in Miami and Gainesville, Florida, and Tucson, Arizona, are currently recruiting 200 cognitively healthy people over age 85. The participants undergo tests and scans in three sessions that profile their cognition and brains. Tests range from timed obstacle courses to memorization challenges, and scans measure such things as the strength of connections between brain areas or the volumes of those areas.

Visscher says she hopes her research reveals what healthy aging brains look like and it teaches us something about how that goes awry in Alzheimer’s. Ultimately, she and everyone else studying Alzheimer’s want to unlock the secret to growing old without losing one’s memory.

“Memory is a function that everybody needs every day to have quality of life, to interact with other people, and to enjoy experiences.” says Lazar. “To study memory means we are not only trying to make the Golden Years as meaningful as possible, but we’re also trying to preserve this function that maintains civilization and society.”

By Cary Estes and Sarah C.P. Wiliams