Michael Schultz carries many titles – student, researcher, teacher, writer.

But for 30 days out of the year, the 28-year-old Minnesota native adds one more to the mix – pumpkin carver.

“I started carving pumpkins when I was old enough to hold a knife,” said Schultz, a fifth-year graduate student in the Immunology theme of the Graduate Biomedical Sciences program at UAB. “My parents taught both my brother and I how to carve very intricate pumpkins at an early age. I never really carved the typical pumpkin faces; I started off carving owls, spiders and different scenes.”

His family each carved two pumpkins every night before Halloween, and on Halloween, they would display all eight pumpkins with varying scenes and animals on their front doorstep. The ritual became a tradition not only for his family, but for their neighborhood.

“My dad was famous for carving a Frankenstein one year,” Schultz said. “We even had one family tell us our home should be featured in the Martha Stewart magazine because our pumpkins were so cool every year.”

As Schultz got older, he attempted more complex pumpkin carvings, trying to mimic what his parents and brother were doing. Eventually, this love of pumpkin carving turned into a “small-scale private business of sorts.” One of his first jobs was working for a railroad museum in Minnesota and when they found out about his side interest, the museum hired Schultz and his brother to carve all of the pumpkins for its annual Pumpkin Patch Train Festival. They carved railroad scenes, haunted mansions, ships and a slew of other designs. Word spread and before he knew it, Schultz had a “mini pumpkin carving empire” as a teenager.

“It sounds like a lot of work, but the reality is we only did this once a year,” he said. “Every now and then we’d carve some for Thanksgiving. The thing about Minnesota is that we could leave a pumpkin outside for a month without it rotting.”

This pumpkin carving venture lasted until he went off to college. As a double major, life got busy so he cut back on carving for businesses, but continued the family tradition.

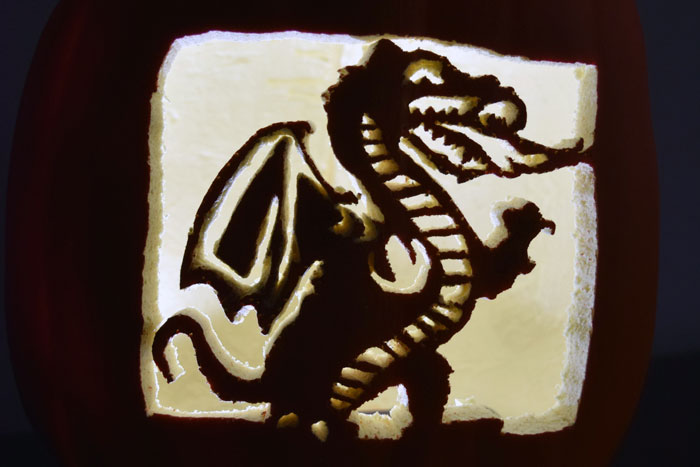

When Schultz moved to Birmingham to begin his graduate studies, he quickly became interested in the pumpkin carving scene his first October. He noticed there were a lot of the typical faces but not much else. So, he randomly carved a pumpkin for his lab and sent out a picture. People started talking about it and it grew.

“People would laugh when they heard I was a professional pumpkin carver, but I always have to correct them,” he said. “There are actual competitions for pumpkin carving, and it’s a big deal to certain groups. There are people who do absolutely stunning pumpkins, so I call myself a pumpkin carving enthusiast attempting to be a true professional.”

Friends started sending around pictures and schools soon got wind of Schultz’s talents. He began volunteering his time carving pumpkins for fall festivals and smaller businesses. Some years there are themes – last year was Alice in Wonderland while this year was Brother’s Grimm. Schultz said he tries to carve at least four or five pumpkins every year for businesses. Word spread to the GBS office and staff there asked if he’d carve some pumpkins to display in the office.

“That is when I discovered you can do a very nice pumpkin out of Styrofoam, called craft pumpkins,” he said. “These Styrofoam pumpkins have the same structure, the same imperfections, and they’ve already been hollowed out for you. All you have to do is carve it and you can keep it all year long. But I also like to make pumpkin pies so I’ll probably not convert to doing Styrofoam pumpkins permanently.”

There is definitely an art to pumpkin carving, and Schultz has perfected his process over the years. First, there is the selection process. Schultz sticks with the standard orange pumpkins – and the bigger, the better. The bigger the pumpkin, the thicker its walls and the harder work it’s going to be, but you can also have more detail and there is more space to work. Plus, if there’s a design that is particularly difficult, it can be blown up and taped to a larger pumpkin, making the details much easier to see and carve, he added.

"When doing detail work, always carve the small pieces first – eyes, scales, feathers, etc. If you follow this rule of thumb, it will make your carving life much easier."

Schultz does not recommend washing pumpkins unless the carver is going to freehand the design. If a pattern needs to be taped to the pumpkin, it will be “nearly impossible” to make it stick if the pumpkin is first washed. Plus, no one really even sees the dirt when it’s dark and lit up, Schultz added.

Once the pumpkin is ready, then comes the design process. While he initially started with patterns purchased from the store, he now creates his own designs. He has also advanced to creating 3D pumpkins, which are some of his favorite because of the lifelike quality of the designs. In terms of tools, Schultz prefers retired dental tools, but the cheap plastic ones purchased from any major store will work just as well. He recommended having a few extra blades on hand because pumpkin carvers will generally break a few blades in the process.

As most people know, one of the first things to be done when carving a pumpkin is hollowing it out. What they might not know is hollowing out a pumpkin means more than just scooping out the inside.

“Depending on how intricate the pattern, the thinner you have to make the wall of the pumpkin,” Schultz said. “You carve out all of the insides and then you pick the side you want your design on and, using a spoon-like object, you scrape out that wall until it is just the right thickness. This is tricky. It’s got to be thin, but not too thin that you bust the whole thing apart when you’re sawing through.”

By thinning out the walls, carving becomes much easier – that’s the biggest trick of pumpkin carving, he added.

The other challenge is decay. The more detailed the pumpkin, the quicker it will rot, and people who carve intricate pumpkins want that art to last a long time, Schultz said. In order for that to happen, coat the carving with Vaseline and then wrap it in Saran Wrap every night. By keeping that moisture in, a very detailed pumpkin should last about 4 days or so in Birmingham, he added.

Another tip Shultz shared is when doing detail work, always carve the small pieces first – eyes, scales, feathers, etc. If you follow this rule of thumb, it will make your carving life much easier.

Now, pumpkin carving is not a quick task. Schultz said to anticipate a simple pattern taking anywhere from 1 to 2 hours, whereas an intricate pattern will probably take closer to 4 or 5 hours. He also said for best results, carve the pumpkin the night before it is to be displayed, and use LED lights. The brighter the light, the better.

While not an incredibly difficult task, and possibly an incredibly frustrating one for novice carvers, the feeling you get when finished is what Schultz said he imagines artists feel when they’re creating a work of art.

“When you get done and it looks exactly like you planned it, it feels absolutely wonderful, but artists are also their own worst critics,” he said. “In the beginning, it rarely came out the way I envisioned, but everyone enjoyed it anyway. For novices, it’s going to be pure frustration, but the thing to always remember when carving a pumpkin is that you’re always going to look at what you carve and think it looks an absolute mess. This is universal for every pumpkin carver. But it isn’t until you put the candle in and turn out the lights that it comes to life.”

Schultz said the best thing to do is keep going, even if you make a mistake.

“Like my mother always says, you’re allowed two swear words per pumpkin,” he said. “After a while, you’ll get to the point where you won’t even need those two.”